Science communication

Science communication is a leadership skill that engages with important aspects of teaching, advocacy, dissemination and career advancement. These bullet points summarize key takeaway notes from presentations by and discussions with Dr. Alex Rose and Dr. Kat Penzkover with the CU Science Discovery Team at the University of Colorado Boulder shared during Day 1 of the Polar Postdoc Leadership Workshop.

- Good science stories have a narrative structure using the “And, But, Therefore” (ABT) method.

- “This happened” And “this happened” But “this happened” Therefore “this”

- Flows from a hook to what the problem is and what was the resolutionIntroduce a hook What is the problem -> Resolution

- “And” and “But” can be short with detailed “Therefore”

- Use the word “but” rather than “however”. Studies show that human’s attention perks up when we use the former.

- The “ABT” method is used in contrast to giving a “string of facts” and was introduced by Randy Olson; more information can be found on it here.

- Sara ElShafie’s Science Through Story provides worksheets on Science Communications (SciComms) and also has recorded sessions.The book Writing Science by Joshua Schimel is also a good resource for improving science narratives.

- “This happened” And “this happened” But “this happened” Therefore “this”

- Be careful about using trigger words as they cause people to stop listening before it is explained

- E.g., avoid explicitly saying the words “climate change” when talking to people who may see it as a political issue. Instead, relate to (or ask about) their personal experiences with changes to their homes/towns, health, farms/soil/crops, recreation activities, etc.

- Avoid the terms “lay” or “layman” when referring to the public because they come across as derogatory.

- The media typically needs who, what, when/where, why should we care?

- Lose the jargon! Words that you use everyday in your work and research will probably not be understood by people outside of academia or even people in your discipline.

- For example, over half (54%) of the U.S. adult population (ages 16-75) reads at or below a 6th grade level (Rothwell 2020). Think about what information you and your average classmate could understand in 6th grade! Challenge yourself to write at this level of reading comprehension (Rothwell 2020).

- Lose the jargon! Words that you use everyday in your work and research will probably not be understood by people outside of academia or even people in your discipline.

Attention spans are shrinking. The average attention span among U.S. adults is just 47 seconds (Mark 2023)! Get to the hook or the “so what” early in your story to keep your audience’s attention.

“Communication is about saying the same thing over and over again” - Dr. Twila Moon

- This is different from always trying to say something new in our research.

- Know your audience and be mindful that different people have different worldviews and cognitive biases. Building a communication strategy around the audience with whom you are engaging will improve the reception of your message.

- COMPASS Scicomm, Inc., developed the message box tool for understanding your audience and crafting your message around them, which you can access here.

- COMPASS also offers interactive training on using the message box and other science communication approaches.

- Don’t answer questions you are not comfortable with answering.

- Use analogies and tell stories.

Community engagement

Community engagement ensures that science involves the communities that are impacted directly by the act of performing research or the outcomes of the study. These bullet points summarize key takeaway notes from presentations by and discussions with Dr. Matthew Druckenmiller and Dr. Twila Moon during Day 2 of the Polar Postdoc Leadership Workshop.

- First and foremost, do no harm. If your research will or could collect data about individuals or communities, make sure you take the appropriate training such as the provided by the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) training on working with human subjects.

- Recognize that people other than academics trained in “western” scientific frameworks hold vast place-based and experiential knowledge that can inform and enhance a collective understanding of the world. Science as a way of knowing is subjective, too. Be open to learning from other people!

- Indigenous Knowledge is its own form of science, based on multi-generational observations of place and experiences in community.

- For scientists working in the Arctic, any research on Indigenous lands and/or about their nutritional, physical, economic, social, cultural, and spiritual relations (e.g., lands, waters, skies, minerals, wildlife, plants, fish, people, communities, knowledges, practices, beliefs) should meaningfully engage with Indigenous communities and their governing bodies early and often (Ellam Yua et al. 2022, Kawerak et al. 2024). Not all Indigenous communities/governments will desire direct involvement or partnership in your research, but they should always be given this opportunity (Kawerak et al. 2024)

- Articles 31 and 32 of the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples expressly afford Indigenous Peoples the right to govern whether and how information about them, “their lands or territories and other resources,” and “manifestations of their sciences, technologies, and cultures” are collected, maintained, shared, and used.

- This concept of Indigenous Data Sovereignty has gained attention across North America in recent years, and many best practice documents exist for western/settler researchers to incorporate and support IDS (Carroll et al. 2020, 2021)

- When starting to do community-based work, it is valuable to do so with mentors who are community members or have established trusting and equitable relationships with communities.

- Postdocs’ spheres of influence only extend so far. Down the line you may have the chance to do things differently, with your own connections. Taking the opportunity to learn how to build relationships within community members from mentors is a great resource.

- Come at partnerships with a long view, because it will take time to build trusting relationships, often two or more years of regularly visiting the community. There are some resources for how to build relationships such as the Equitable Arctic Research: A guide for Innovation

- Planning or pre-proposal grants can help fund relationship-building and partnering to develop a community-driven research project. These grants allow you to gather in partnership, get to know each other, and write a proposal together. A current example from NSF can be found here.

- Ensure that partners know they can say “no” to part or all of the project and back out at any time. This is part of an ethical research practice known as Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC). Your project must be flexible enough to adapt to partner concerns, needs, and recommendations because FPIC is an ongoing process. The Food and Agriculture Administration of the United States (FAO) provides a manual for project practitioners titled: Free Prior and Informed Consent An indigenous peoples’ right and a good practice for local communities

- Before engaging with a community, do your research. Learn about the community’s history, culture, social dynamics and current social-political issues. Know when it is not the right time to be engaging with that community.

- Before traveling to the community, check with a local point of contact about the current situation (water shortage, funerals, etc.) and whether your visit needs to be rescheduled.

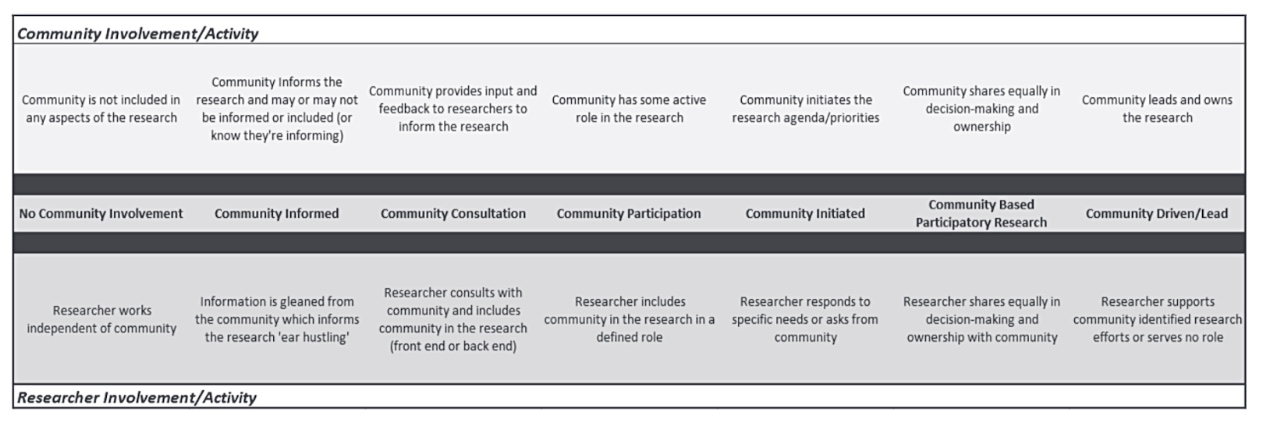

- Community engagement lies on a continuum. Determine the extent of community involvement and partnership (ownership) that your project desires or requires prior to initiating your engagement (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. The continuum of community engagement in research: involvement and activity, Key et al. 2019, Figure 2.

- Community engagement is a constant, life-long learning process

- Soft skills (interpersonal communication, social insight, facilitation, conflict mediation, leadership, delegation, organization) are key for engaging/building relationships with communities. For example, when hosting a community meeting or workshop, it is important to:

- Provide refreshments to participants. These include coffee/tea, snacks (fresh fruit and veggies are always good for communities in rural/remote areas with limited access to affordable produce) or a meaningful/cultural food from your own home/place of residence.

- Provide incentives like door prizes if your funding allows. Consider tagging onto relevant community meetings or partner with a local organization that can help with incentives and refreshments.

- Avoid holding a meeting during important community events like a town hall, funeral, or cultural festival. Contact local offices to know the community calendar and ask when you should visit.

- Work with local leaders to have an Elder give the welcoming/prayer - but make sure you can pay them or offer them a gift for their time!

- Should youth be there? Yes! Youth are the future. Consider bringing youth into these spaces. Learn about or be aware of the benefits from this and the challenges of engaging with diverse age groups in the same space.

Scientific Engagement for research in other locations

Scientific engagement serves to disseminate science to diverse communities and individuals of various fields. These bullet points summarize key takeaway notes from discussions throughout the Polar Postdoc Early Career Workshop.

- Engage people who aren’t typically engaged in environmental science and/or conservation, like urban area residents, Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC), organized religious groups, and youth.

- Schools are a great option and way to engage. Programs like Skype a Scientist can help you to engage classrooms all over the USA.

- Engage communities around or near your home or place of residence that will be affected by changes in the location you do research (like Antarctica).

- Similar principles apply to those of Community Engagement

- Know your audience, research the local history and current issues, reach out to mentors or others who have worked with that or a comparable group.

- If engaging with a school, reach out to teachers and figure out what your visit could provide for them, how your knowledge fits within their curriculum. Might need to contact the administration or principal for those school first.

- Can apply for funding through Research Experiences for Teachers (RET) Supplement Opportunity to include K-12 educators and two-year college science faculty in research. The former Polar Trek program at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) has experience with taking teachers to the field. The Polar STEAM office at the Oregon State University might be a good resource to connect with as well.

References:

Carroll, S.R., Garba, I., Figueroa-Rodríguez, O.L., Holbrook, J., Lovett, R., Materechera, S., Parsons, M., Raseroka, K., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., Rowe, R., Sara, R., Walker, J.D., Anderson, J. and Hudson, M. (2020). The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Data Science Journal, 19(1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2020-043.

Carroll, S.R., Herczog, E., Hudson, M., Russell, K. and Stall, S. (2021). Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR Principles for Indigenous data futures. Scientific Data, 8(1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00892-0.

Yua, E., Raymond-Yakoubian, J., Daniel, R.A. and Behe, C. (2022). A framework for co-production of knowledge in the context of Arctic research. Ecology and Society, 27(1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.5751/es-12960-270134.

Kawerak, Inc., Chinik Eskimo Community, King Island Native Community, Native Village of Brevig

Mission, Native Village of Council, Native Village of Diomede, Native Village of Elim, Native Village of Gambell, Native Village of Koyuk, Native Village of Mary’s Igloo, Native Village of Saint Michael, Native Village of Savoonga, Native Village of Shishmaref, Native Village of Teller, Native Village of Unalakleet, Native Village of Wales, Native Village of White Mountain, Native Village of Shaktoolik, Nome Eskimo Community, Stebbins Community Association, and Village of Solomon (2024) Kawerak-Region Tribal Protocols, Guidelines, Expectations & Best Practices Related to Research. Prepared by the Kawerak Social Science Program and Sandhill.Culture.Craft. Nome, Alaska.

[online] Available at: https://www.kawerak.org/knowledge

Key, K.D., Furr-Holden, D., Lewis, E.Y., Cunningham, R., Zimmerman, M.A., Johnson-Lawrence, V. and Selig, S. (2019). The Continuum of Community Engagement in Research: A Roadmap for Understanding and Assessing Progress. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 13(4), pp.427–434. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2019.0064.

Mark, G. (2023). Attention Span: A Groundbreaking Way to Restore Balance, Happiness and Productivity. Harlequin.

Rothwell, J. (2020). Assessing the Economic Gains of Eradicating Illiteracy Nationally and Regionally in the United States. [online] Available at: https://www.barbarabush.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/BBFoundation_GainsFromEradicatingIlliteracy_9_8.pdf.

This section was orchestrated by Dr. Emily Tibbett, Dr. Maria Luisa Sánchez Montes, and Dr. Taylor Stinchcomb.