Collaboration

This section is based on presentations by and discussions with Dr. Matthew Druckenmiller, Dr. Eran Hood, Dr. Anne Gold and Dr. Allen Pope.

New collaborations often begin with networking. Conducting informational interviews allows you to meet a colleague and learn about their work without the expectation of future collaboration. These connections can be particularly valuable when made in person. If inquiring to strangers about possible collaborations over email, then consider providing the following information:

- proposal and project timeline,

- general roles of each potential collaborator,

- funding level estimate, and

- explanation of why they are the right collaborator for the project.

It is good to invite and incorporate all partners as early as possible. Pilot projects or grant supplements specifically for partnership building can be great first steps before embarking on a large project.

Once a conversation begins, there are many questions to consider when deciding whether to commit to a collaboration:

- Are the project’s overall goals and those of your collaborators aligned with your own goals?

- Does the group have sufficient expertise and resources to reach the goal?

- Do you have the time now and are you willing to commit the required time in the future at the expense of other opportunities?

- Will you enjoy working with these partners?

The answers to these questions can help with decisions to accept or decline new collaborative opportunities. It is always okay to say, “No, thank you,” and that capability, if not interested or able at the time, should build with time.

If you do decide to submit a proposal, it is critical for all partners to communicate their needs and goals. This is especially important when collaborating with people from various research disciplines or professional sectors. For example, team members may need to be paid at different levels to allow their participation. Similarly, each partner might value different aspects of a project’s outcomes. Working in such a team can be very rewarding and productive. After submitting a proposal, it is good practice to communicate the funding decision to all involved in its preparation.

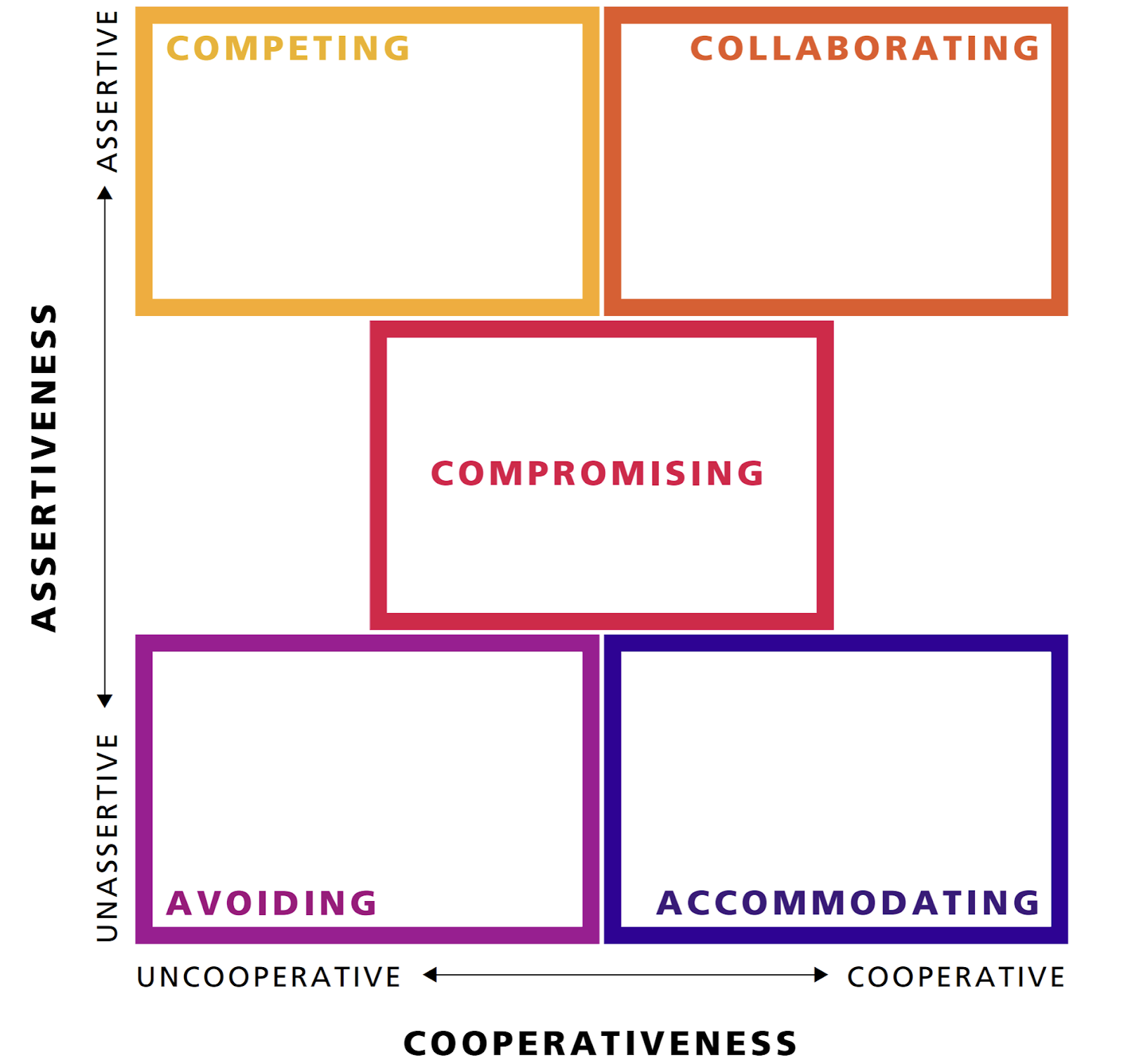

Establishing group norms and expectations can be valuable as a collaborative science project progresses. It is good practice to maintain regular communication to keep everyone updated about progress and delays. In addition, defining authorship requirements early and revisiting them regularly can reduce the incidence of authorship conflicts (e.g., Albert and Wager 2003). But various conflicts inevitably arise, and they are resolved effectively in fruitful collaborations. There are five general ways to address conflict, each with varying levels of assertiveness and cooperativeness (Fig. 1). Competing, collaborating, compromising, avoiding, and accommodating all have pros and cons.

Fig. 1. The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument assesses a person’s behavior during conflict along dimensions of assertiveness and cooperativeness. Adapted from Thomas and Kilmann (2008).

Inclusive mentoring

This section is based on presentations by and discussions with Dr. Bec Batchelor and Dr. Anne Gold.

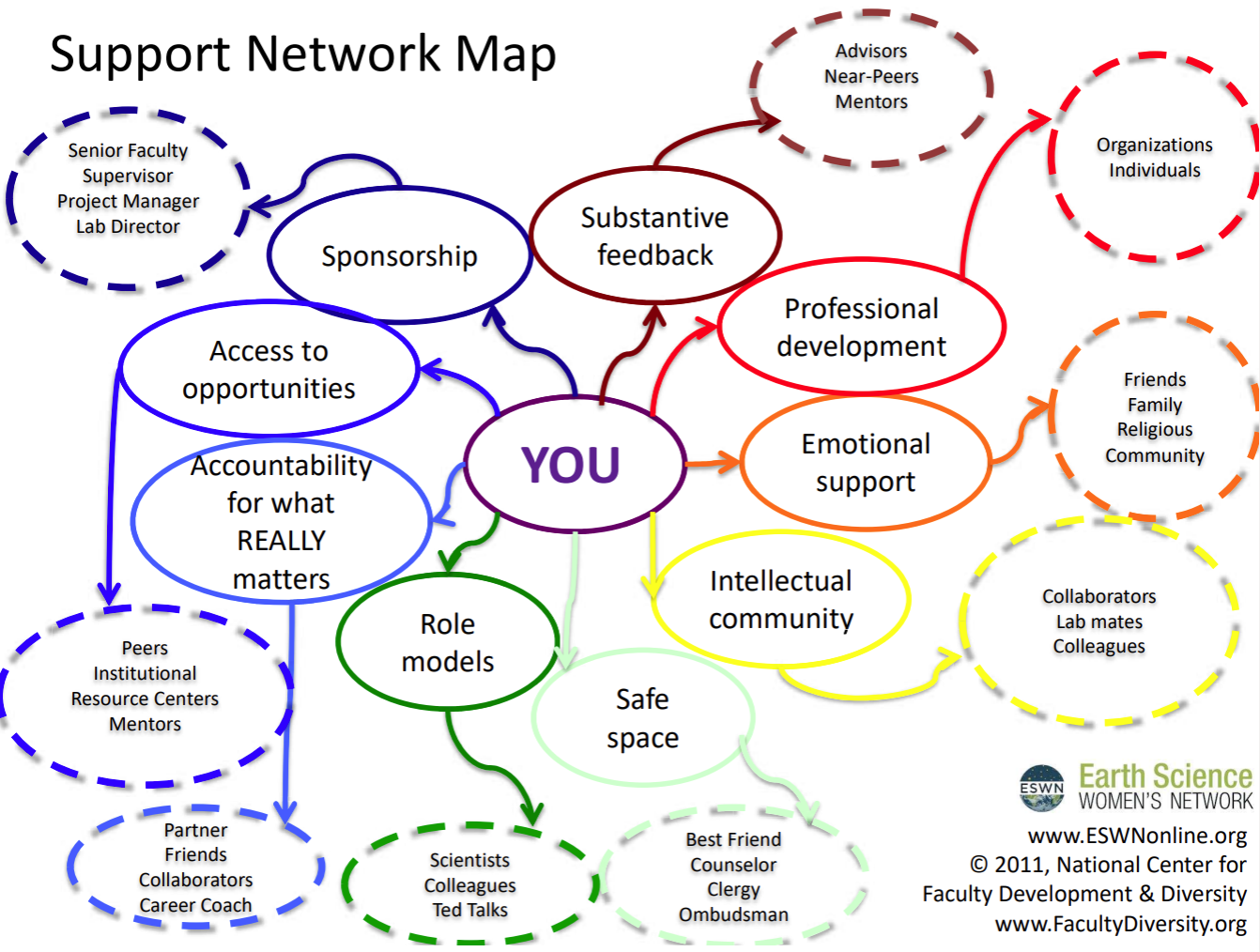

Postdocs rely heavily on mentorship, and a supportive network of mentors can be invaluable. There are many different types of support that you may need during your career (Fig. 2), and filling out a mentoring (or ‘support network’) map can be a valuable exercise for identifying the people who can help support different aspects of your career (Earth Science Women’s Network). Not every person can fill every role, but having people in your corner to provide anything ranging from substantive feedback to emotional support can go a long way. Try filling out your own mentoring map here: https://mirjamglessmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Mentoring_map_01.png.

Fig. 2. The Support Network Map illustrates different types of mentoring that a researcher may need throughout the course of a career. Adapted by Earth Science Women’s Network from National Center for Faculty Development and Diversity.

In addition to finding their own mentors, postdocs take on important roles as mentors themselves, and successful mentor/mentee relationships start at the beginning. In early conversations, it is important to ask about a mentee’s expectations and needs, including those related to accessibility. Such discussions are an opportunity to establish boundaries, for example to establish the ideal time to connect and to agree on a mode of future communication. A mentoring agreement completed up front in consultation with a mentee can be a very useful tool. While initial meetings should include establishing a mentee’s work plan, effective mentoring often also includes sharing a bit about oneself and getting to know your mentee. The GEO REU Resource Center hosts many useful resources for mentors, including a list of questions that mentors and mentees may want to ask one another.

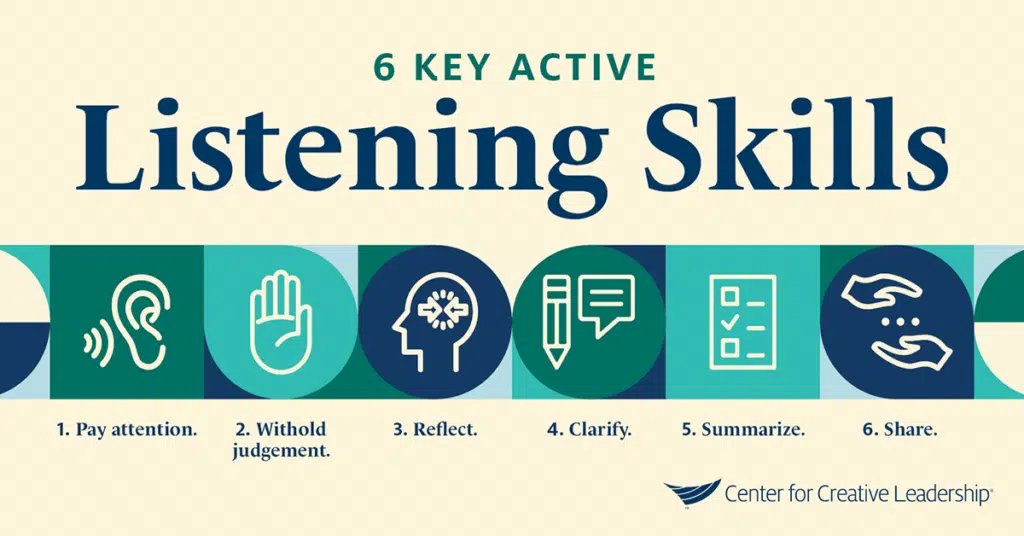

Successful and inclusive mentors are effective communicators. This involves being an active listener, which entails paying attention, withholding judgment, reflecting, clarifying, summarizing, and sharing (Fig. 3). Specifically, asking clarifying questions is a good approach for gaining understanding of a mentee. For example, saying, “Can you tell me more about what you meant?” can help prompt a mentee to explain themselves more clearly. The Center for Creative Leadership provides additional information on active listening techniques, which can be practiced in mock exercises with colleagues. When corrective feedback is needed, it can be helpful to identify the behavior, explain its impact, and set expectations. Here is an example:

- Observe behavior: “I noticed that sometimes you leave food out in our office.”

- Explain impact: “When you do this, it attracts ants.”

- Set expectation: “I would like you to store your food in the refrigerator down the hall.”

Regardless of whether you follow this three-step approach, strive to be kind when providing feedback (and in all aspects of mentoring).

Fig. 3. The Center for Creative Leadership identifies six active listening skills, which will benefit mentors.

Participants shared many perspectives on mentoring at the 2023 Polar Postdoc Leadership Workshop. Here are a few examples that reflect how individuals view the important role of a mentor:

- Mentors open doors, provide a sense of belonging, and build confidence for their mentees.

- Mentors help mentees become more who they are, not more like the mentor.

- Mentors are vulnerable and share stories of their own failures.

- Mentors empower mentees to solve problems, rather than solving problems for them.

The discussion demonstrated that there is no one-size-fits-all approach for a successful mentor/mentee relationship. Postdocs are at an important stage in their development when they can benefit greatly from mentorship while also building their own skills to become effective, inclusive mentors.

This section was developed by Dr. Alex Ravelo, Dr. Devon Dunmire, and Dr. Jack Conroy.